The DEBBIES project has been awarded 2nd place in the Newcastle University Open Research Awards 2025. This recognition means a lot because it is the collective outcome of eight years of student-led research, shared openly and built collaboratively. This blog post celebrates the students whose work built DEBBIES — and highlights the science that their openness has made possible.

From small projects to a global resource

What began as a handful of undergraduate projects in 2017 has now grown into a global open resource, a mechanistic modelling framework, a teaching tool, and a foundation for multiple scientific discoveries across ecology, evolution and conservation.

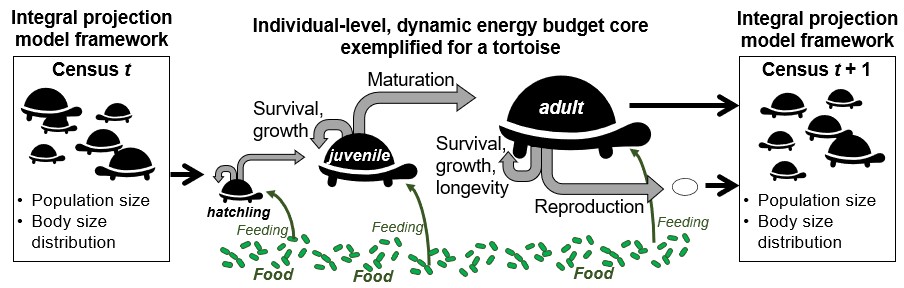

DEBBIES dataset now includes >330 species, from mites to manta rays, with traits describing growth, mortality and reproduction. Because these traits feed into dynamic energy budget integral projection models (DEB-IPMs) [1] (Figure 1), they allow us to calculate population growth, demographic resilience, and responses to new environmental conditions.

Figure 1. Schematic of a Dynamic Energy Budget Integral Projection Model (DEB-IPM). A DEB-IPM is a population model that tracks cohorts of female individuals in a population feeding on a resource, capturing the demographic rates of survival, growth, reproduction and the relationship between parent and offspring size, using eight life history parameters [1].

All of this was made possible thanks to student researchers. For example, Dr Marjolein Toorians was the very first to contribute to DEBBIES, helping to build the first DEB-IPM [1]—the backbone of every DEB-IPM analysis that followed. Dr Sol Lucas contributed the largest number of species and co-authored the Scientific Data paper that formally describes the DEBBIES dataset [2]. The most recent contributor, Victoria Dixon, contributed >130 bony fish species and linked DEBBIES to morphology.

Many more students have added species, traits, metadata, validation scripts and new ideas. Because of them, DEBBIES is not just a dataset — it is a living, growing, open scientific community.

What DEBBIES has enabled so far: scientific papers & discoveries

Open data and open models mean open possibilities. The DEBBIES framework has already supported several major papers — each revealing something new about life-history strategies and how species respond to environmental change.

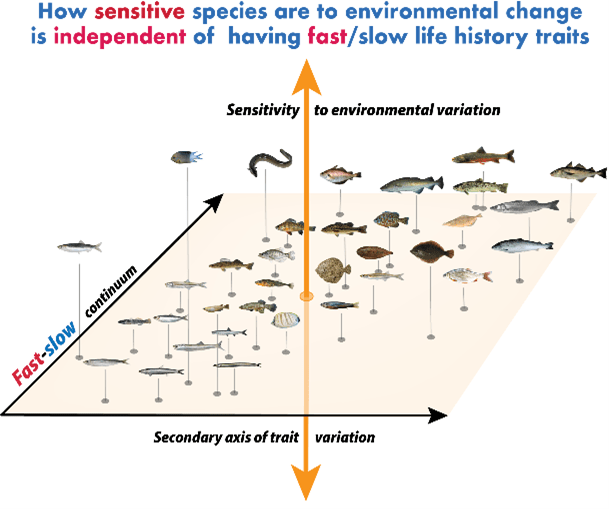

1. Life-history strategies do not always predict population responses [3]. Using DEBBIES, we discovered that in ray-finned fish, classic life-history axes (fast–slow, reproductive strategies) often fail to predict how populations respond to environmental variability (Figure 2). This challenges long-standing assumptions in ecology and shows the need for mechanistic, process-based models.

Figure 2. Trait patterns in ray-finned fish can be structured along two major axis of life history variation, while population sensitivity to environmental variation occupies its own axis, i.e. it is an emergent outcome that is independent of the patterns in the species traits [3]. Credit: Mark Rademaker.

2. Life-history traits do not explain IUCN threat status in reptiles [4]. Analysis revealed that reptile conservation risk cannot be inferred from traditional life-history strategies. This highlights the limits of purely trait-based conservation approaches.

3. Feeding levels reshape life-history strategies in sharks, skates and rays [5]. A major insight made possible because DEBBIES includes many data-deficient elasmobranchs. We showed that feeding level — not just evolutionary background — drives reproductive output and generation time. This has important implications for fisheries management and climate-change vulnerability.

4. Population growth ≠ population resilience in estuarine tubeworms [6]. Using DEB-IPMs, we found that estuarine tubeworm species (Figure 3) with high population growth may still be poorly resilient to disturbances. Another example where mechanistic demography reveals patterns that classical theory misses.

Figure 3. Marine tubeworms are often used as environmental indicators. Our new research [6] suggests that tubeworms can reveal signs of stress not just by disappearing, but through changes in how they grow, reproduce and develop.

Broader conceptual insights: energy allocation rewires ecological predictions

Across these papers, a unifying message is emerging. How organisms allocate energy between growth and reproduction fundamentally shapes life-history strategies, and this mechanistic trade-off is essential for forecasting population responses to environmental change. This is exactly what the DEBBIES modelling framework was built to capture.

A tool for research, teaching, and exploration

DEBBIES isn’t only a research dataset — it’s a hands-on educational tool. Try the DEBBIES Demographic Model Explorer (Shiny App), and learn more about how to use it here.

Why the Open Research Award matters

The Open Research Awards celebrate research that is not just rigorous, but also accessible, transparent, and community-minded. I’m incredibly grateful to the team behind the awards for highlighting the value of student-led open science. This award truly belongs to the many students who contributed to DEBBIES, and to the colleagues who have supported and championed open practices throughout the project.

Looking ahead

DEBBIES is still growing. Next steps include:

- Expanding to more taxa and environments

- Refining energetic models with temperature dependence

- Applying DEB-IPMs to real-world conservation challenges

- Integrating new student projects every year

And of course: keeping everything open.

References

[1] Smallegange IM, Caswell H, Toorians MEM, de Roos AM. 2017. Mechanistic description of population dynamics using dynamic energy budget theory incorporated into integral projection models. Methods in Ecology and Evolution 8: 146-154

[2] Smallegange IM, Lucas S. 2024. DEBBIES Dataset to study life histories across ectotherms. Scientific Data 11: 153

[3] Rademaker M, van Leeuwen A, Smallegange IM. 2024. Why we cannot always expect life history strategies to directly inform on sensitivity to environmental change. Journal of Animal Ecology 93: 348-366

[4] Stevenson EA, Lucas S, McGowan PJK, Smallegange IM, Mair L. 2025. To what extent can life history strategies inform species conservation potential? Ecology and Evolution 15: e71488

[5] Lucas S, Berggren P, Barrowclift E, Smallegange IM. 2025. Changing feeding levels reveal plasticity in elasmobranch life history strategies. Ecology Letters 28: e70201

[6] Smallegange IM, Edwards LHA, Attle A. 2025. Population performance and resilience in polychaetes as environmental indicators of estuarine ecosystems. In: Estuaries – Dynamic Ecosystems at the Land-Sea Interface (Ed. Pereira L). Rijeka: InTechOpen. DOI: 10.5772/intechopen.1011169

Wonderful article and a huge congratulations to all the students involved, a well deserved award!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks Nicola!

LikeLike